The plot is straightforward enough. Three girls, Minal, Falak and Andrea, join a few guys at their resort for dinner and drinks after a rock concert. Something transpires and the girls flee the scene after hitting a boy almost fatally with a bottle. While we are not shown what happened, it’s implied heavily that Minal was molested. Alone and scared of the incident, the girls just want to move on with their lives.

Meanwhile, the boys Rajvir, Dumpy and Ankit hatch plans of revenge. They are going to show these modern ‘characterless’ girls their place in this world. The threats and the harassment begin. The girls finally go to the police, which make matter worse for them. Minal finds herself in prison in charge of murder and the girls truly hit rock bottom. Help comes as Mr. Deepak Sehgal, a retired lawyer, takes on their case.

The first half of the movie is a slow stretch–establishing the premise, the characters, their dynamics and desperation. It’s like elastic being pulled back, and then it snaps in the second half. The courtroom drama is the moral center of the movie. It takes on the trite and over-used ‘she was characterless, so she deserved it’ approach head on. The defense aids in establishing that she may be characterless (whatever that truly means)–but did she consent to sex? Emphasis on consent is the core theme.

The movie also calls out on the inherent feudal mindset that prevails on today’s urban men that appear deceptively modern. Rich, educated abroad, trotting about in designer wear, they still don’t see women as equals or people with free will.

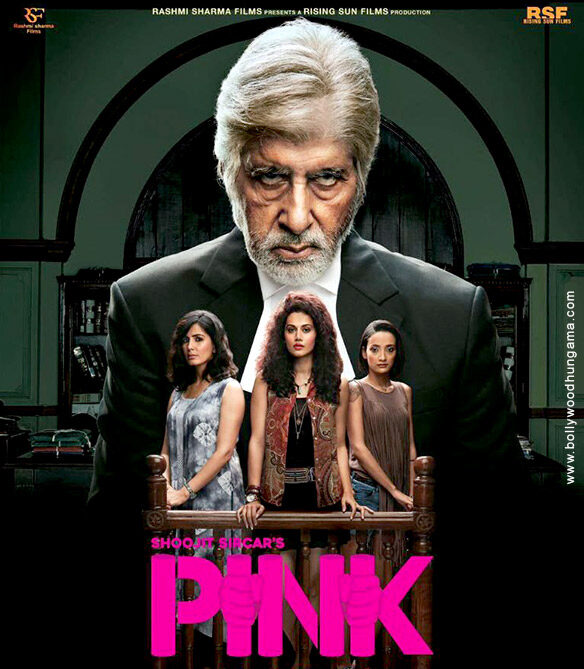

Taapsee Pannu as Minal and Kriti Kulhari as Falak bring in fine, nuanced performances. Pannu does a phenomenal job in the portrayal of an assault victim. Sexual assault may not always leave physical marks, but the emotional scars are as important. She easily outshine Amitabh Bachchan in every scene (a side note – his towering presence was really not required on the poster of a movie about a woman’s issue). The movie is low in melodrama until Bachchan appears on the scene (just kidding—well, not really). I do like the fact that even then; the focus remains on the girls. Mr. Sehgal’s character breaches on the edge of sermonizing but often stops short, which is a relief. It’s important for movies to drive social messages without occupying the pulpit.

Some narrative decisions seem very deliberate. As the audience, we never see the actual incident till the ending credits roll. Along with the court, we rely on the testimony of the girls and the witnesses. It’s a parallel to real life where often in cases of molestation there are no witnesses and the onus of establishing the incident often falls on the traumatized victim. The movie makes an important point of mentioning that consent is important even if it’s the women in question is your wife, a pointed barb at the lack of laws around marital rape.

It’s important to note that this movie is not about just about rape. It deals with a very specific type of incident about a very specific section of society. The focus of the movie is rather on the deep-seated patriarchal values that drive men in India to assume themselves as the proprietors of woman and self-appointed judges on their transgressions and habits – ‘You drink, so you are fair game. You smile freely at me, so you are fair game. You refuse me, how dare you, you slut! Let me show you who I am!’ These values extend to the police force whose job is to protect its citizens. The condescending and dismissive inspector, who discourages Minal from filing her original complaint; the rude and unsympathetic female police officer who arrests the girls without proper investigation.

Minal, Falak and Andrea are women just living their lives. What happened to them continues to happen to a lot of girls like them. And they are not as lucky as having a Mr. Sehgal help them.