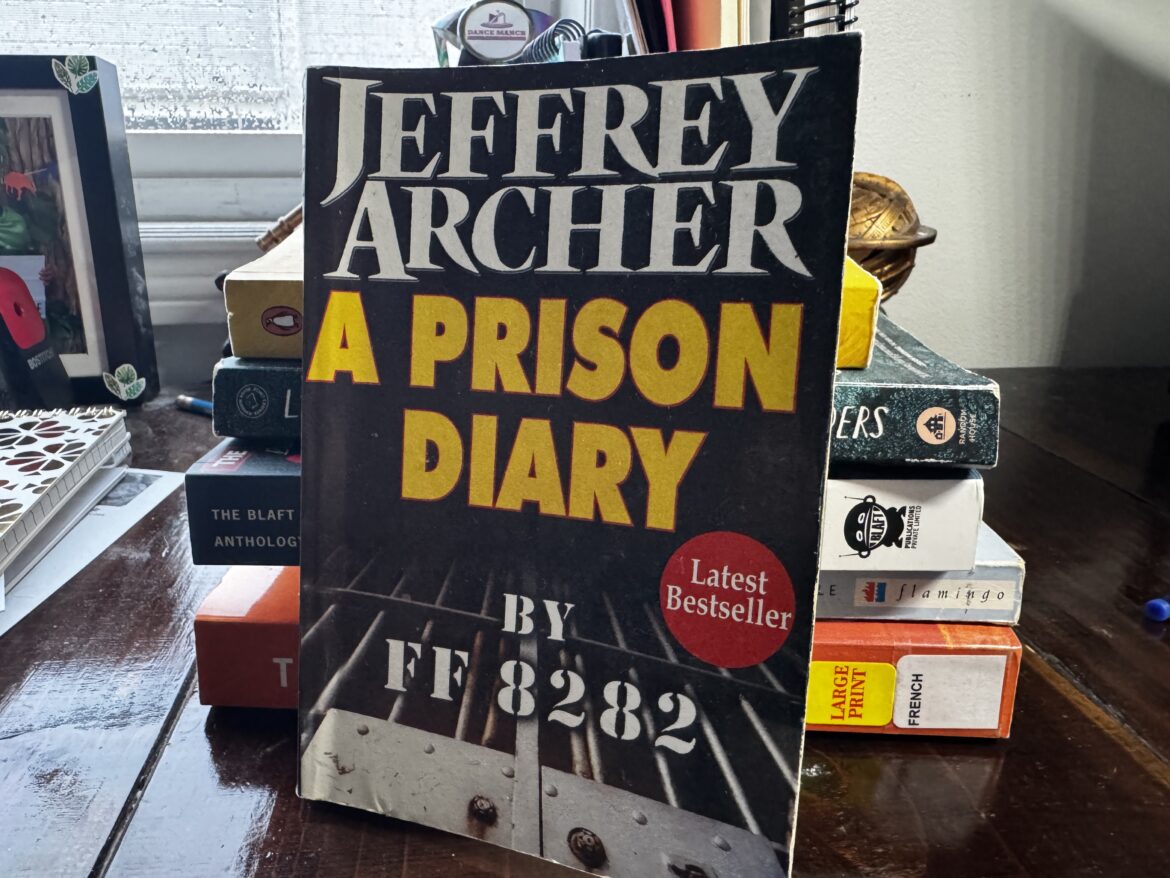

This book has been sitting on my bookshelf for easily over a decade. Somewhere down the line I outgrew Archer’s storytelling style, and with no genuine sympathy for a politician in jail, I never got around to reading it.

For reasons unclear, I finally managed to pick it up and read it through the weekend, and I can confidently give this journal a solid 3 stars.

“Prisoners and guards routinely line up outside my cell to ask for my autograph, to write letters, and to seek advice on their appeals.” – Jeffery Archer

A Prison Diary (Hell) is clearly not one of the best or most profound accounts of imprisonment. It’s however, easy to read and shows an accessible outsider-looking-in viewpoint of the British prison system. As the outsider is an elite, a best-selling writer and a member of parliament no less, Archer’s prison diary portrays a clash of two different worlds.

“I have a feeling that being allowed to write in this hellhole may turn out to be the one salvation that will keep me sane.” – Jeffrey Archer

To retain his sanity and kill the hours, Archer assiduously documents his experience in HMP Belmarsh, a high-security prison that is more of a waystation in case before he is assigned his actual prison. Archer obviously paints himself in a very positive light, and several assertions of innocence are made. I have neither context nor curiosity about the actual circumstances of his arrest, so I ignore these assertions and move on.

For me, the most interesting aspect of his prison journal is the day-in-the-life element of it. The schedule, the meals (the fact that he can’t make himself eat any of the prison slop and choses to live off cheese and biscuits is another pointer of his coming from a different world) and the various activities that the incarcerated are kept engaged in.

His extensive interviews with other prisoners, throws a light on several issues plaguing the UK’s judicial system. Archer dons a documentarian’s hat as he learns and explains the extensive drug trade that sustains the prison life. There is also the trade of goods and services, from something as harmless as a bottle of mineral water to a gram of cocaine. And then, of course, there is a commentary on the inefficiency of how sentences are meted out, poorly paid staffing that run the prisons, and the failure of the judicial system to actually help criminal reform.

Again, nothing is entirely original or unheard of, but the matter-of-fact tone that Archer adopts makes this an easy read. Enough that I am tempted to check out the second part of the published diary series.